SOLID Series : Open-Closed Principle

Have you ever found yourself fighting through legacy code, trying to find the right line to modify in order to get that new feature to work? If you have, the Open-Closed Principle might be just right for you.

Definition

Bertrand Meyer requested in 1988, that software “modules should be both open for extension and closed for modification.”

Let’s define what this actually means.

Open for extension When a module is open for extension, it is possible to extend the behaviour of that module, to satisfy changing requirements. Basically, we can change what the module does.

Closed for modification A module is closed for modification, when the module itself does not change. When the source code does not change, the module is closed.

How to

So how can we change something, without touching it? The key is to use Abstraction or code to an interface, not an implementation.

Think about it, if the module is not working with a concrete implementation, but rather an abstract interface, we can drop in any implementation we want, as long it conforms to the defined interface.

OCP Violation

First let’s look at an example of OCP Violation in order to understand why we can do better.

Let’s imagine that we’re building a chat app. We set up a ChatWindow component, which waits for the user’s input and sends it to the server.

And implementation of that function might look like this:

handleSubmit() {

const userInput = this.getUserInput();

this.sendToServer(userInput);

this.clearInputField();

}We get the input of the user, send it straight to the server and clear the textfield. The application launches and everything works fine. Soon after our company decides to increase the profit by selling an In-App-Purchase that let’s users encrypt their messages.

By looking at the reviews from our users, we see that app does not handle offline situations really well, since the messages never get send to the server and are lost in space and time. We decide to check for an offline situation, and save messages to the disk in order to send them as soon as the user is connected again.

That’s the code of our new version:

handleSubmit() {

const userInput = this.getUserInput();

if (this.isConnected() && this.shouldUseEncryption()) {

this.sendEncrypted(userInput);

} else if (this.isConnected()) {

this.sendToServer(userInput);

} else {

this.saveOffline(userInput);

}

this.clearInputField();

}We had to open up our ChatWindow class in order to add the requested behaviour. Therefore we are violating the Open-Closed Principle. Our module is not closed for modification.

What’s wrong with this approach anyways?

Hard to understand and to change Look at this if block. Every new feature needs to be added here. It gets more complicated and harder to understand. It’s pretty easy to make a mistake and unintentionally break something.

It’s more than likely that in a big application, there won’t be just one of those if statements, but rather multiple ones spread in different source files. Handling encryption will also be needed when handling the reception of messages, for instance. Imagine how easy it will be to forget one of those if cascades.

__Hard to reuse If one day we decided to reuse our code in a new, fully encrypted chat and just reuse the parts dealing with the UI (getting the input and clearing the text field)? Well, we could, but we also need to bring our initial, non-encrypted server implementation with us. Why? Because we depend on it’s implementation.

Hard to test In a test, you most likely don’t want to make and actual http request or deal with I/O (writing to the disk), because those things are error prone. You probably want to use a mock implementation to make sure your code is handing of the user’s input correctly. It’s nearly impossible to do that, with our current design.

Conforming to the OCP

So, what can we do in order to conform to the Open Closed Principle? Generally, there are two common approaches: The Strategy Pattern and the Template Method Pattern.

Strategy Pattern

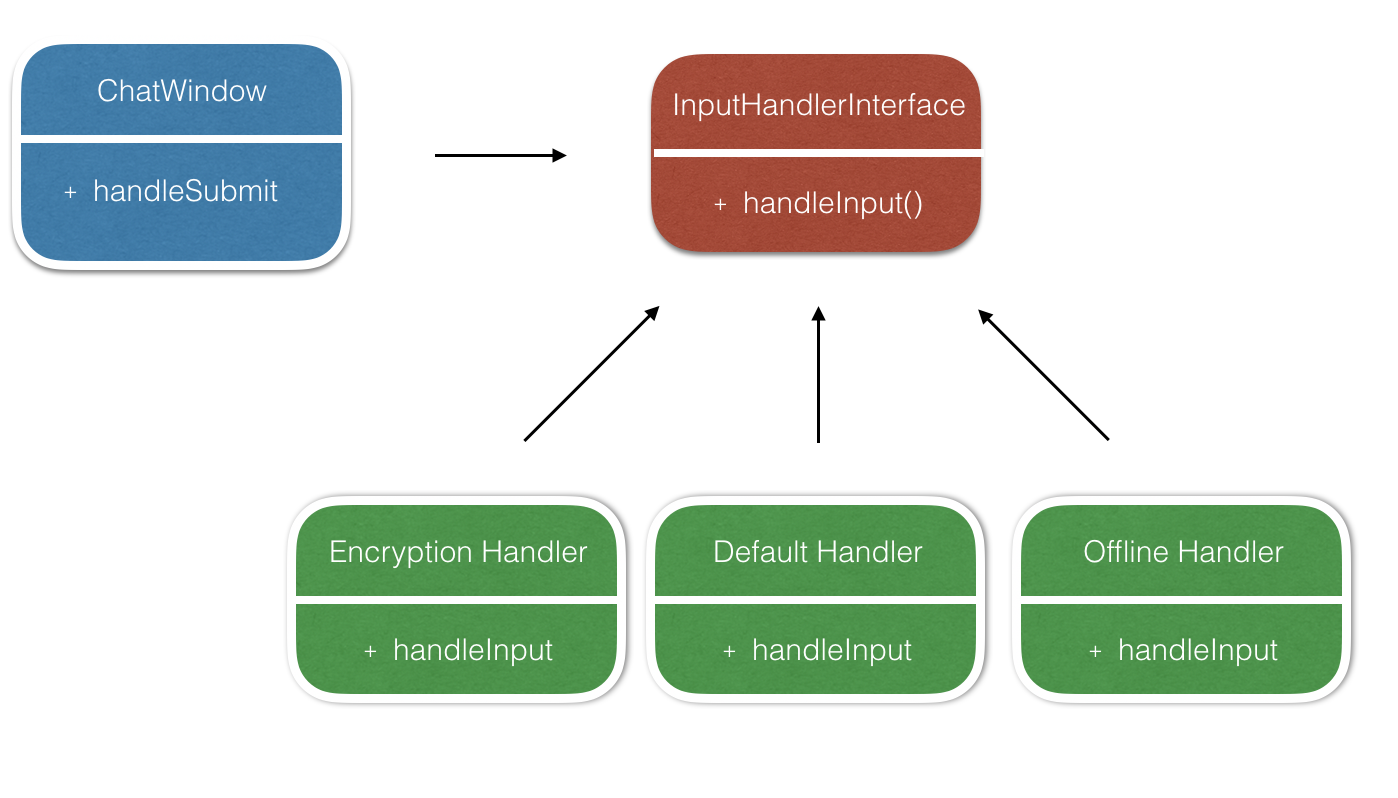

The [Strategy Pattern] suggests that you create an interface, in order to selected the right “strategy”, i.e. the right implementation at runtime. Let’s the how we could implement it:

We define an interface with one method handleInput on it. Now, we pull out all implementation details for offline handling, encryption and no encryption from ChatWindow into their own files and let them implement the InputHandlerInterface. The ChatWindow itself is now only responsible for getting the user input and clearing the text field. It hands the data to one of the implementations and has done it’s job.

How to select and strategy

You might wonder how the ChatWindow knows which implementation to choose. It doesn’t. And it shouldn’t. In order to make it truly closed from future changes all it should know is it’s abstraction (the interface). This gives the ChatWindow the ability to work with any implementation as long as the interface is respected.

So where does it get the implementation from then? A common way to do this, is to use the [Factory Pattern]. The factory is now in charge of finding out whether the user is offline or needs encrypting and returns the correct implementation.

The ChatWindow will be given the correct implementation when it’s created. This is called Dependency Injection.

interface InputHandler {

handleInput(userInput: string);

}

class ChatWindow {

private _inputHandler: InputHandler;

constructor(inputHandler: InputHandler) {

this._inputHandler = inputHandler;

}

handleSubmit() {

const userInput = this.getUserInput();

this._inputHandler.handleInput(userInput);

this.clearInputField();

}

}

class OfflineHandler implements InputHandler {

handleInput(userInput: string) {

//save offline

}

}

class DefaultHandler implements InputHandler {

handleInput(userInput: string) {

//send to server

}

}

class EncryptionHandler implements InputHandler {

handleInput(userInput: string) {

//encrypt and then send to server

}

}If we take a look at the handleSubmit method in ChatWindow we notice that those if/else statements are gone. How gorgeous is that?

Even better, if we need a new feature that handles the data differently, all we have to do, is create that new feature. We don’t have to mess with ChatWindow anymore. It is now closed for modification.

We also can safely reuse our code in a new application, because it no longer depends on any implementation, therefore we don’t need to carry over stuff we don’t need.

Obviously, something has to change in order to get that new feature working, though. In this case, we also have to adjust the factory to return the new implementation when it’s needed.

Template Method Pattern

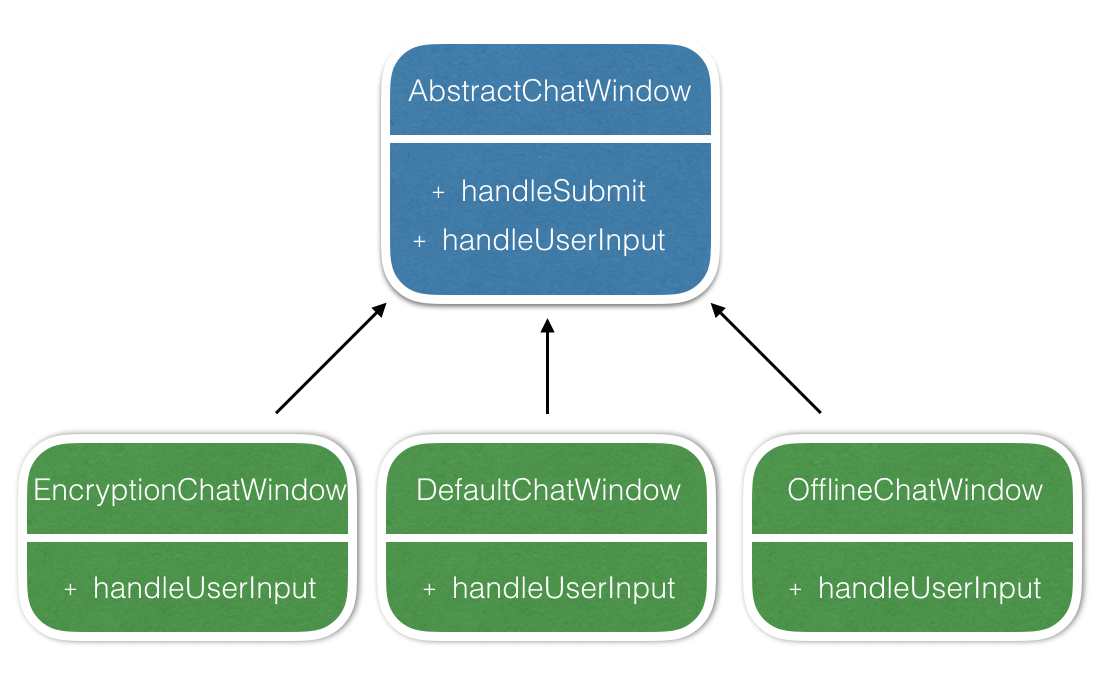

[This] approach also uses abstraction in order to conform to the OCP. The idea here is to create a template implementation which provides hooks (call abstract methods) that can be overridden by subclasses in order to change the behaviour.

The code for getting the user input and clearing the text field is now in a template method in the abstract class AbstractChatWindow. It has an abstract method (the hook) called handleUserInput that needs to be overridden by the derived classes, in order to change the implementation. We create a subclass for Offline handling, encryption and no encryption handling.

abstract class AbstractChatWindow {

abstract handleUserInput(userInput: string);

handleSubmit() {

const userInput = this.getUserInput();

this.handleUserInput(userInput);

this.clearInputField();

}

}

class OfflineChatWindow extends AbstractChatWindow {

handleUserInput(userInput: string) {

//save offline

}

}

class DefaultHandler extends AbstractChatWindow {

handleUserInput(userInput: string) {

//send to server

}

}

class EncryptionChatWindow extends AbstractChatWindow {

handleUserInput(userInput: string) {

//encrypt and then send to server

}

}Again, our code conforms to the Open-Closed Principle. In order to add a new feature, we can simply add a new subclass. The template method code remains unchanged.

The problem with OCP

Before you spin up your IDE to add abstractions in your while codebase, in order to never touch legacy code again, I’d like you to think this through.

Is it really possible to write code that is resident to any kind of change? The truth is, it can’t be. If the ChatWindow requires different rules for clearing up the text field, it is not closed to modification, because we haven’t protected ourselves from that kind of change. We only protected the code from changes regarding the user input.

The problem is, that we can not predict any change that will ever occur and therefore we can never fully close a module.

What we can do, tough, is close our module against the same changes.

Handling Change

In order to determine the parts that are susceptible for change, Robert “Uncle Bob” Martin suggests a workflow that aligns well with scrum.

-

Build something simple without unnecessary abstractions Treat every feature as if it won’t change.

-

Deliver early and often Get the new features in front of the users as soon as possible.

-

Wait for changes When the user request changes, refactor the code by creating abstractions that will protect yourself from any future changes of that kind.

This workflow aligns so well with scrum, because scrum teams work in short iterations to add new features. Each iteration should start with a small design session, to determine the abstractions needed, before implementing the new features. Each iteration’s goal should be to increase the conformation to the Open-Closed Principle.

Conclusion

The Open-Closed Principle allows us to write robust code by removing the necessity to edit (open) a class in order to add new features.

Understanding the code in each module is easier, because the number of if/else statements is reduced.

By removing the dependency on concrete implementation, we promote the reusability of our module.

Although we can never predict any change that might occur, we can learn from past changes, and protect ourselves of them by following scrum methodologies.